(Vol 1, pp. 292-299) NY: Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1856.

(Vol 1, pp. 292-299) NY: Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1856.

Men hermits have been frequently heard of, but a woman hermit is of rare occurrence. Nevertheless, Ridgefield could boast of one of these among its curiosities. Sarah Bishop was, at the period of my boyhood, a thin, ghostly old woman, bent and wrinkled, but still possessing a good deal of activity.

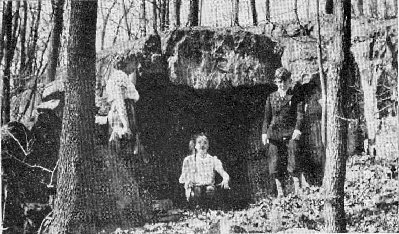

She lived in a cave, formed by nature, in a mass of projecting rocks that overhung a deep valley or gorge in West Mountain. This was about four miles from our house, and was, I believe, actually within the limits of North Salem; but being on the eastern slope of the mountain, it was most easily accessible from Ridgefield, and hence its tenant was called an inhabitant of our town.

This strange woman was no mere amateur recluse. The rock-bare and desolate—was actually her home, except that occasionally she strayed to the neighboring villages, seldom being absent more than one or two days at a time. She never begged, but received such articles as were given to her. She was of a highly religious turn of mind, and at long intervals came to our church, and partook of the sacrament.

She sometimes visited our family—the only one thus favored in the town – and occasionally remained overnight. She never would eat with us at the table, nor engage in general conversation. Upon her early history she was invariably silent; indeed, she spoke of her affairs with great reluctance. She neither seemed to have sympathy for others, nor to ask it in return. If there was any exception, it was only in respect to the religious exercises of the family: she listened intently to the reading of the Bible, and joined with apparent devotion in the morning and evening prayer.

Circa 1945 photo of Sarah Bishop’s Rock

From “When Our Town Was Young”

I have very often seen this eccentric personage stealing into the church, or moving along the street, or wending her way through lane and footpath up to her mountain home. She always appeared desirous of escaping notice, and though her step was active, she had a gliding, noiseless movement, which seemed to ally her to the spirit-world.

In my rambles among the mountains, I have seen her passing through the forest, or sitting silent as a statue upon the prostrate trunk of a tree, or perchance upon a stone or mound, scarcely to be distinguished from the animate objects – wood, earth, and rock–around her.

She had a sense of propriety as to personal appearance, for when she visited the town, she was decently, though poorly clad; when alone in the wilderness she seemed little more than a squalid mass of rags. My excursions frequently brought me within the wild precincts of her solitary den. Several times I have paid a visit to the spot, and in two instances found her at home.

A place more desolate – in its general outline – more absolutely given up to the wildness of nature, it is impossible to conceive. Her cave was a hollow in the rock, about six feet square.

Except a few rags and an old basin, it was without furniture–her bed being the floor of the cave, and her pillow a projecting point of the rock. It was entered by a natural door about three feet wide and four feet high, and was closed in severe weather only by pieces of bark.

At a distance of a few feet was a cleft, where she kept a supply of roots and nuts, which she gathered, and the food that was given her.

She was reputed to have a secret depository, where she kept a quantity of antique dresses, several of them rich silks, and apparently suited to fashionable life: though I think this was an exaggeration. At a little distance down the ledge, there was a fine spring of water, in the vicinity of which she was often found in fair weather.

There was no attempt, either in or around the spot, to bestow upon it an air of convenience or comfort. A small space of cleared ground was occupied by a few thriftless peach-trees, and in summer a patch of starveling beans, cucumbers, and potatoes. Up two or three of the adjacent forest-trees there clambered luxuriant grape-vines, highly productive in their season. With the exception of these feeble marks of cultivation, all was left ghastly and savage as nature made it.

The trees, standing upon the tops of the cliff, and exposed to the shock of the tempest, were bent, and stooping toward the valley – their limbs contorted, and their roots clinging, as with an agonizing grasp, into the rifts of the rocks upon which they stood. Many of them were hoary with age, and hollow with decay; others were stripped of their leaves by the blasts, and other still, grooved and splintered by the lightning.

The valley below, enriched with the decay of centuries, and fed with moisture from the surrounding hills, was a wild paradise of towering oaks, and other giants of the vegetable kingdom, with a rank undergrowth of tangled shrubs. In the distance, to the east, the gathered streams spread out into a beautiful expanse of water called Long Pond.

A place at once so secluded and so wild was, of course, the chosen haunt of birds, beasts, and reptiles. The eagle built her nest and reared her young in the clefts of the rocks; foxes found shelter in the caverns, and serpents reveled alike in the dry hollows of the cliffs, and the dank recesses of the valley. The hermitess had made companionship with these brute tenants of the wood. The birds had become so familiar with her, that they seemed to heed her almost as little as if she had been a stone.

The fox fearlessly pursued his hunt and his gambols in her presence. The rattlesnake hushed his monitory signal as he approached her. Such things, at least, were entertained by the popular belief. It was said, indeed, that she had domesticated a particular rattlesnake, and that he paid her daily visits. She was accustomed – so said the legend – to bring him milk from the villages, which he devoured with great relish. The facts in respect to this Nun of the Mountain were indeed strange enough without any embellishments of fancy. During the winter she was confined for several months to her cell. At that period she lived upon roots and nuts, which she had laid in for the season. She had no fire, and, deserted even by her brute companions, she was absolutely alone, save that she seemed to hold communion with the invisible world.

She appeared to have no sense of solitude, no weariness at the slow lapse of days and months: night had no darkness, the tempest no terror, winter no desolation for her. When spring returned, she came down from her mountain, a mere shadow–each year her form more bent, her limbs more thin and wasted, her hair more blanched, her eye more colorless. At last life seemed ebbing away like the faint light of a lamp, sinking into the socket.

The final winter came—it passed, and she was not seen in the villages around. Some of the inhabitants went to the mountain, and found her standing erect, her feet sunk in the frozen marsh of the valley. In this situation, being unable, as it appeared, to extricate herself—alone, yet not alone—he had yielded her breath to Him who gave it! The early history of this strange personage was involved in some mystery. So much as this, however, was ascertained, that she was of good family, and lived on Long Island.

During the Revolutionary war—in one of the numerous forays of the British soldiers—her father’s house was burned; and, as if this were not enough, she was made the victim of one of those demoniacal acts, which in peace are compensated by the gibbet, but which, in war, embellish the life of the soldier. Desolate in fortune, blighted at heart, she fled from human society, and for a long time concealed her sorrows in the cavern which she had accidentally found. Her grief – softened by time, perhaps alleviated by a vail of insanity—was at length so far mitigated, that, although she did not seek human society, she could endure it.

The shame of her maidenhood—if not forgotten—was obliterated by her rags, her age, and her grisly visage in which every gentle trace of her sex had disappeared.

She continued to occupy her cave till the year 1810 or 1811, when she departed, in the manner I have described, and we may hope, for a brighter and happier existence.